by Aniket Bhushan and Rachael Calleja

Published: February 6, 2017

*This post is a summary of findings and preview of a forthcoming research paper.

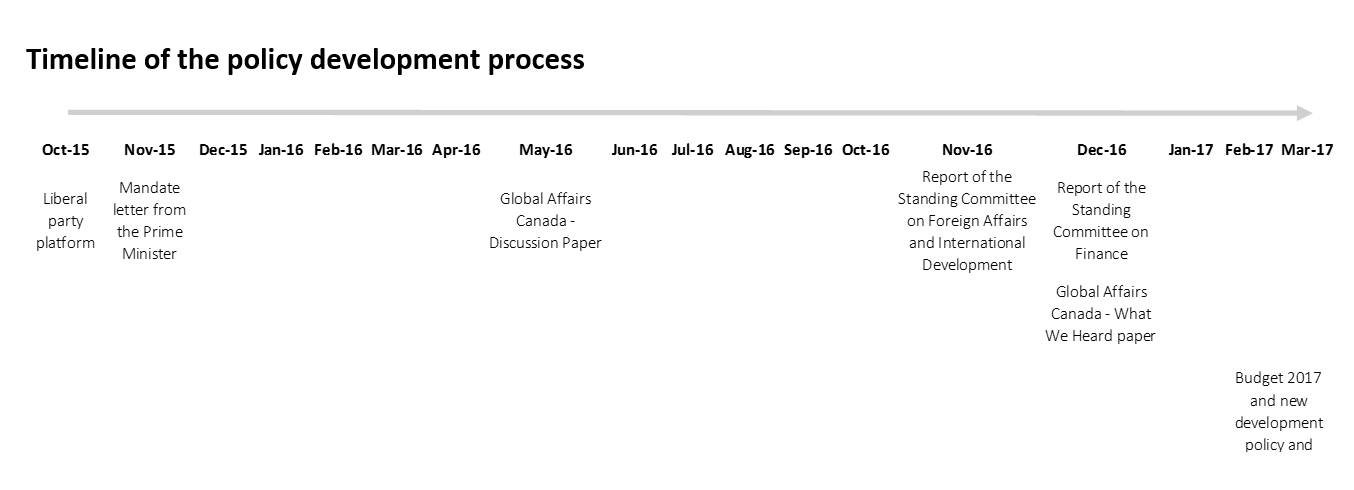

In May 2016, Global Affairs Canada launched a policy review of Canada’s international assistance. The aim of the international assistance review (IAR) is to come up with a new policy and funding framework for Canada’s approach to global development. This is the first such review in Canada in at least a decade.

The IAR presents an interesting case study in policy development. From the perspective of a policy development continuum the emphasis on public consultations presents an example of government attempting to go beyond the typical inform + consult end of the spectrum to engage + co-create.

The outcome of the review – a new policy and funding framework – is expected alongside the upcoming Federal Budget 2017 (in February or March). A timeline of the process is given below.

About this analysis: Motivations & Approach

The literature on how and why policy change happens, when it happens, and why it takes the course it takes is wide-ranging, but leaves important gaps (an exhaustive review is beyond the current scope but available in our forthcoming paper).

Major theories range from “incrementalism” which emphasizes path-dependence; to the “policy streams” literature which emphasizes the need for a policy ‘window of opportunity’; to “advocacy coalitions” which highlights the importance of a diversity of actors working to ‘transform beliefs into policy’; to the “garbage-can model” which argues policy changes are less intentional and a function of ‘solutions chasing problems’ (Lindblom, 1959; Kingdon, 1984; Sabatier, 1988; Cohen, March and Olson, 1972).

Each approach offers insights into Canada’s IAR but leaves gaps. While the literature helps explain how and why policy changes happen, it leaves gaps regarding the content of policy change i.e. what is actually changing. It therefore also leaves gaps in terms of the eventual impact of the process of policy change.

Our interest is in unpacking:

- Assumptions behind the need for change – i.e. the thinking that underpins what needs to change and why.

- How these have evolved through the process – especially given the emphasis on ‘public consultation’, which, much of the literature cautions is often a form of “tokenism” (Arnstein, 1969; Bishop and Davis, 2002).

- How the external environment is taken into account (or not) in the process of policy change?

- Why this approach or process will lead to the needed change?

- How and where we might find evidence or indications of change?

In order to get at these areas we need a flexible framework. For our specific purpose we also need a framework that can be used reflexively and inter-temporally, i.e. to look back on the case years from now as the real impact of a new policy and funding framework, especially in an area like development, will only materialize over the medium to longer term.

Our aim is to make a contribution towards at least two objectives:

- To set up a framework which, while necessarily subjective, is transparent and flexible, such that it could also be applied to other domains (e.g. defense policy which has similarly undergone a consultation and review, or trade policy which underwent a similar process under the auspices of the Trans-Pacific Partnership consultations). Our framework could then be used for comparative analysis – which is especially relevant given the overlaps across foreign policy domains and the emphasis on ‘whole-of-government’ approaches.

- To ensure some form of external accountability, as well as systematic and balanced reflection as a check against ‘tokenism’.

Our approach

Our sample for this analysis is restricted to official sources, directly linked to the IAR process, released by relevant government departments and therefore reflective of formal positions. Relevant parliamentary committee reports, and the party platform of the Liberal government (given it made some mention of perspectives and positions on development) are also included.

Documents covered in this analysis include:

- Liberal Party Platform

- Mandate Letter to the Minister of International Development and La Francophonie

- International Assistance Review Discussion Paper

- Report of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development

- What We Heard (consultation output)

- Report of the Standing Committee on Finance

The new policy and funding framework, and Budget 2017 statement on Canada in the World (if relevant), will be added to this list when released.

While not included here, other official sources including Budget 2016, official Departmental Performance Reports (DPRs) and Reports on Plans and Priorities (RPPs), as well as other reporting to parliament on official development assistance spending (ODA accountability act) were also analyzed.

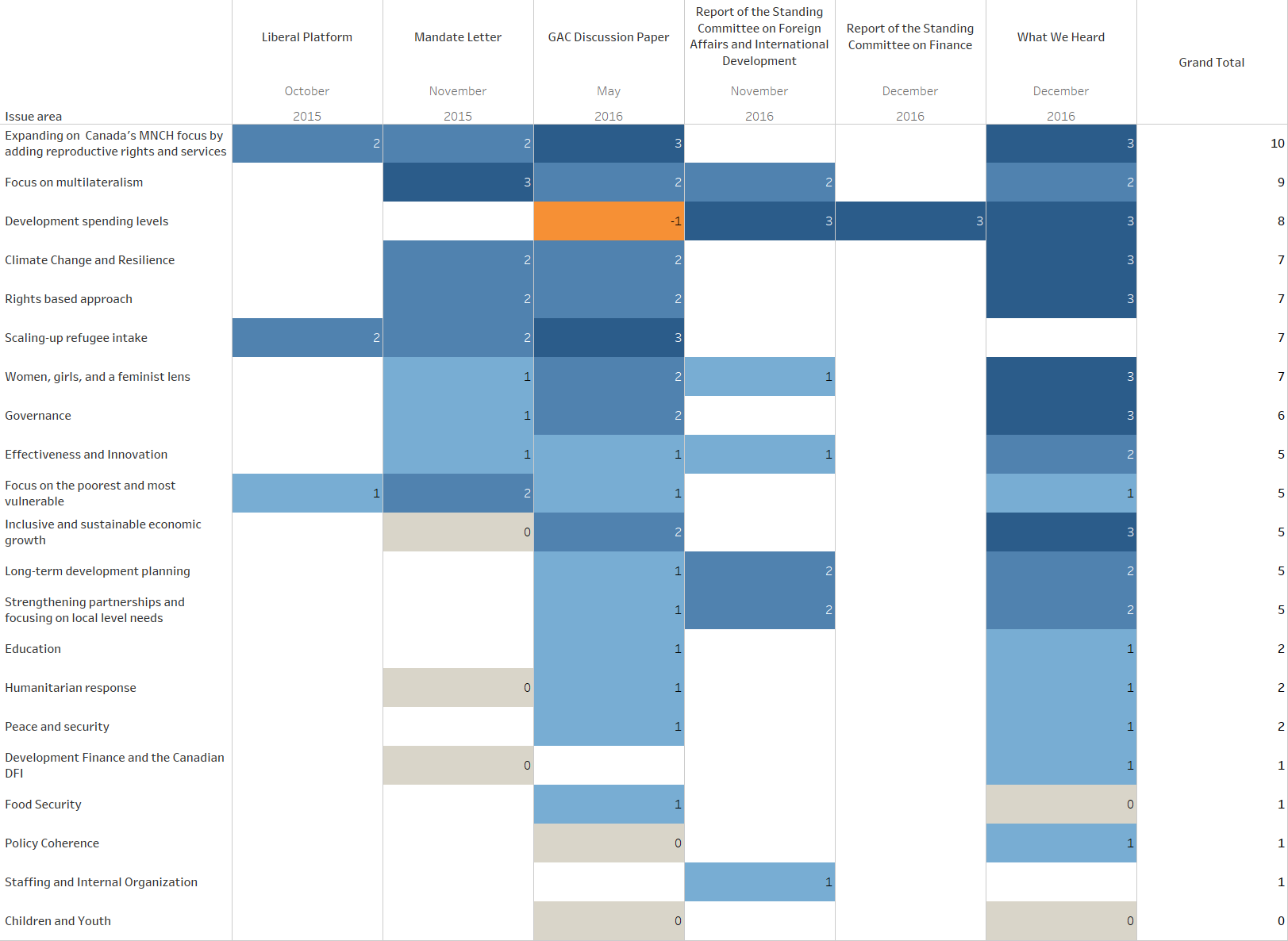

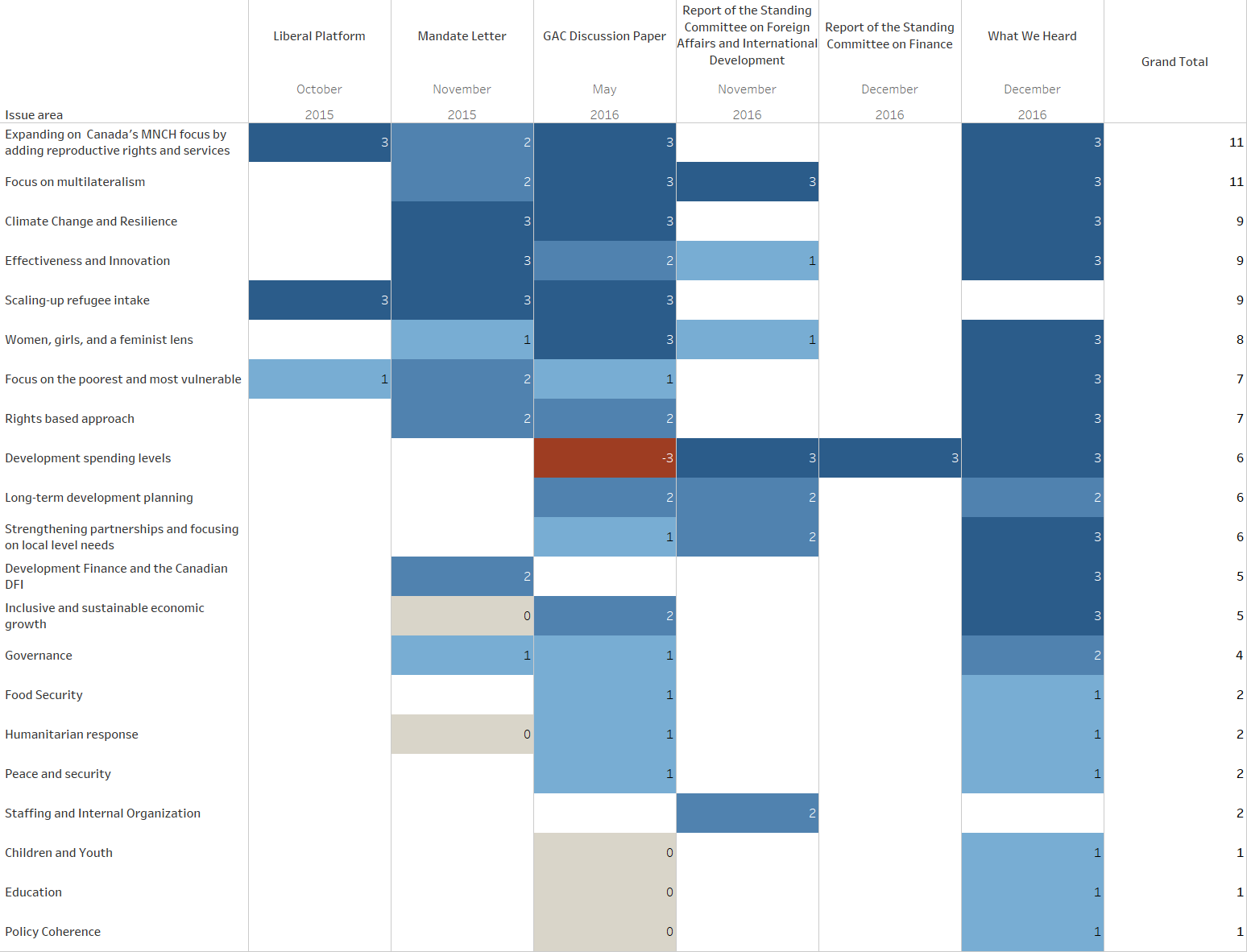

The first step in our analysis was to develop a list of issue areas to be coded. These are recurrent themes, priorities, concepts, ideas and proposals that appear across the sources.

In some cases the phrasing was modified to better group the plethora of issues that are discussed across sources in order to analyze how they evolve over the course of the process (for e.g. early on in the Liberal party platform ‘focusing on the poorest’ and ‘focusing on Africa’ appeared interchangeably to contrast against the Conservatives, however later on the emphasis turned primarily to ‘focusing on the poorest’, hence these categories were combined. In the opposite direction early on in the process ‘expanding on Canada’s MNCH initiative’ was a clear priority, however, through the course of the process the broader articulation of ‘women and girls and a feminist lens’ emerged as a separate arguably overarching priority. Hence these were divided.).

In all we identify 21 key issue areas.

Our framework

Our framework covers 3 key aspects at the moment, with a fourth to be added once the IAR outcome is released.

Each issue area was coded, based on the reference statement(s) appearing in the given source, on a scale from -3 to 3.

The 3 aspects analyzed at the moment are:

- Potential for change from the status quo: identifies the degree to which the area represents a break from the status quo. In this case ‘0’ implies no change, ‘3’ implies significant change.

- Level of development of the issue area: scores the extent to which key ideas are developed and detailed. ‘3’ implies targets and proposals have already been outlined.

- Impact on expectations: identifies whether expectations for change (by the way the issue is raised and discussed) are ratcheted upwards or downwards. ‘-3’ implies expectations are being lowered (rarely the case in such a process) and ‘3’ implies expectations are heightened.

The 4th and perhaps most important aspect to be added to this analysis is our criteria for assessing the impact and outcome of Canada’s IAR and new framework.

Given the relatively broad and generalist approach taken in Canada’s IAR, the criteria for assessing its impact will also need to be broad.

Canada’s review, unlike others – for instance the UK which has also recently undertaken an aid review with similar objectives but a very different approach (a comparison we analyze elsewhere) – seems less about a hard-nosed analysis of strategic needs and opportunities, comparative advantages, or the most effective and efficient means of delivering international assistance, and more about how Canada’s engagement is branded and framed.

For instance the emphasis on ‘women and girls’ and taking a ‘feminist lens’ is already a clear outcome of the process. The change to be expected in this area is a move away from a ‘checkbox approach‘ to more nuanced analysis and consultations at every stage. Yet, what this means in practice for, say, the duration and process required to vet and approve projects, choice of implementing partners, or the impact on the non-core costs of a project, are not evident either from official sources or IAR discussions. The analysis is also devoid of a nuanced higher order theory of change that articulates just how these project level changes aggregate up and interact with the wider socioeconomic context in the countries where Canada (typically a mid-sized donor among several players) will implement its new feminist approach.

Analytically speaking, identifying such changes and attributing the same to the IAR will be extremely difficult (if not impossible). While the laudable emphasis on women, girls and a feminist lens – which is corroborated by our analysis – is certainly welcome, parsing out what this means in terms of what changed or where to look for evidence of changes will be extremely difficult because as we have shown elsewhere Canada’s international assistance is already highly “gender focused” according to the government’s own official data. A finding backed up by the OECD’s analysis which shows that Canadian aid is about twice as focused on gender equality and women’s empowerment as the OECD-DAC average and in this regard Canada ranks second only to Sweden.

The above caveat(s) complicate our framework. That said we propose the following questions as a minimum criteria for assessing the impact and outcome of Canada’s IAR and new framework:

- Does the IAR move the needle in terms of increasing Canada’s overall development budget?

- Did a greater share of the portfolio go towards areas prioritized in the IAR; did the composition of the portfolio change at all?

- Did the IAR impact how or how much of the global burden/need Canada took on (e.g. share of refugee settlement, contribution to humanitarian emergencies, global health etc.)?

- Were any new areas of Canadian comparative advantage identified via the IAR, or new capacity/expertise developed as a result of the same?

- Was there any discernible change in how Canada delivered international assistance post the IAR, for e.g. from the perspective of developing country, multilateral, global and local development partners?

- Are there areas Canada no longer focused, post IAR, or examples of ‘shift away’ or de-emphasizing attributable to the outcomes of the IAR?

The above remain proposed criteria. We welcome further discussion and feedback on the same.

The criteria need to be broad but robust enough that we can apply them years from now (for e.g. at the end of the current Liberal government mandate in 2019), and practical in that the cost of gathering additional data on the same is not prohibitive.

Preliminary findings

In this section we share findings from two areas: “potential for change from the status quo”; and “impact on expectations”.

We also discuss two examples of how our framework and coding are applied.

Our datasheet, comprising the 3 aspects of the framework covered so far is shared at the end (this is a live document and will be updated once the new framework is released).

Potential for change from the status quo (click to enlarge)

In the heat-map above (and below) issue areas are listed on the left (y-axis) and our key sources are organized chronologically on the top (x-axis). As is obvious some areas have pervaded the process more so than others.

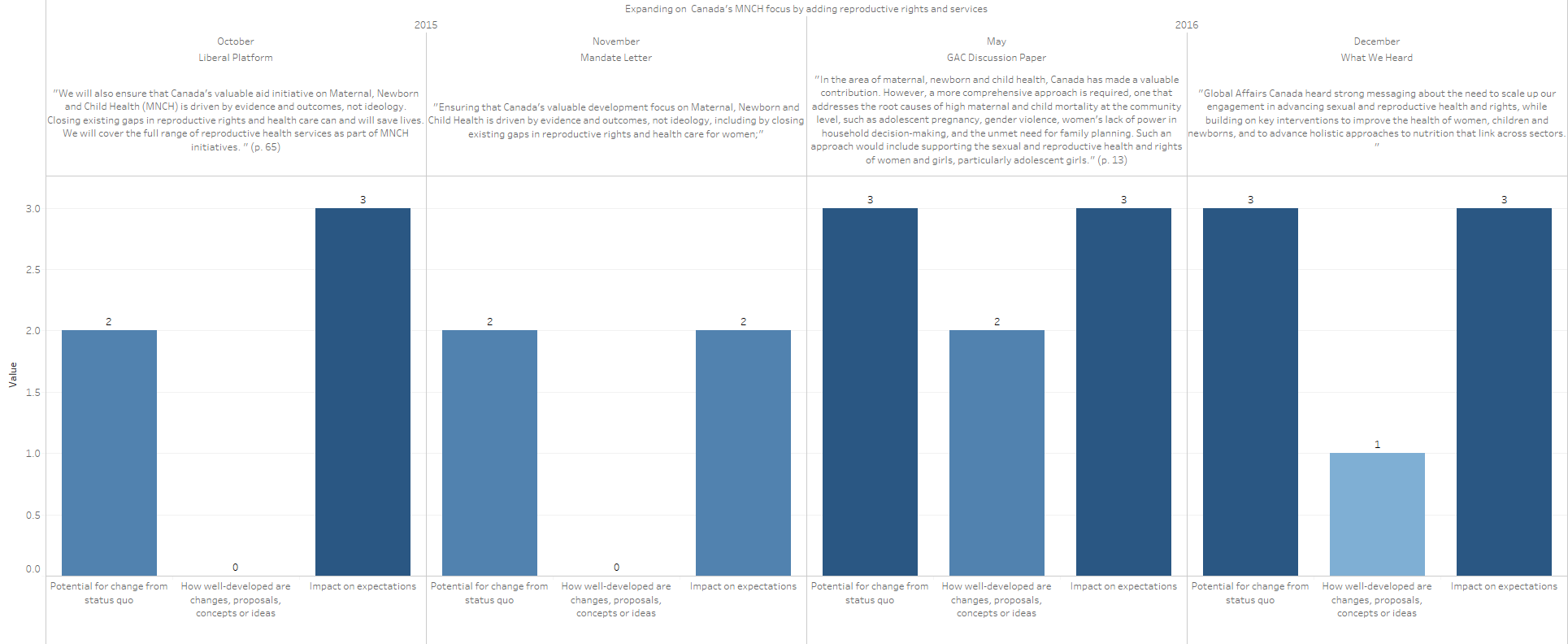

“Expanding MNCH”

Expanding on Canada’s maternal newborn child health (MNCH) initiative by adding support for the full range of reproductive rights is the most obvious area in terms of change from status quo. It also ranks highest in terms of expectations – i.e. delivering with new programming and funding (which Canada has already started doing to some extent), will be the least surprising outcome.

As the trend graph (below) shows, earlier documents such as the Liberal platform and the Prime Minister’s Mandate Letter both mentioned expanding MNCH. However ideas around the same were further developed in the GAC discussion paper and corroborated by the public consultation outcome.

Delivering on expanding MNCH and attributing the same to the IAR is a foregone conclusion. The only question is how and how far will the new policy and funding framework go.

Having a sense of the wider context is essential to assess this outcome of the IAR. It is worth keeping in mind that expanding and contracting what is covered within MNCH has long been a function of ideological and political football – commonly known as the “global gag rule” on donor funding for sexual and reproductive rights and services including abortion and family planning, also known as the “Mexico City Policy”.

It works as follows. The “gag rule” severely restricts donor funding for sexual and reproductive rights. Each incoming socially conservative administration imposes it, while each socially progressive government rescinds it. It was first imposed by the Regan administration, rescinded by the Clinton administration, reimposed by the Bush administration, only to be rescinded by the Obama administration.

This matters because one of the first executive orders of the Trump administration was to reimpose the “gag rule” (in fact the farthest reaching version to date). The US is by far the largest aid provider in this area. Initial estimates show that the new “gag rule” on abortion causes an immediate $600 million gap in family planning funding, and potentially places $9 billion in health aid at risk.

Canada is not immune. The previous Conservative government under PM Harper, which made MNCH its signature aid initiative, limited support for sexual and reproductive rights (and abortions specifically). The Liberal government has sought to fill this gap. It can be argued this is merely a Canadian version of political football on the “gag rule”; which would temper its attribution to the IAR policy development process.

It is relatively easy to play up this area for a domestic audience, than for Canada to lead on it globally. Other donors such as the Netherlands, are already taking the lead by responding with a new international fund for safe abortions aimed at countering the impact of Trump’s re-imposition of the “gag rule”.

Expanding MNCH is not an abstract issue. Impacts of past impositions of the “gag rule” are well researched and documented. For example, a 20 country study by Stanford University examining the impact of the “gag rule” in sub-Saharan Africa found that countries with high exposure to the policy experienced a relative decline in the use of modern contraceptives and (ironically) an increase in the induced abortion rate.

The real question for Canada is how far its new policy and funding framework will go in this area. In large part this comes down to a question of resources.

When the US last imposed the “gag rule” this caused a major contraceptive supply crisis in Ethiopia. Ethiopia is one of Canada’s largest aid recipients and according to our analysis one the largest in the MNCH area specifically. However, globally, the US provides nearly 15 times the amount of aid Canada provides in the area of family planning; and in Ethiopia the US aid budget is about 7 times the size of Canada’s.

Given funding from the largest global donor in this specific area is suspended with immediate effect, if Canada’s expansion of MNCH is going to have a tangible impact even just in one of its longstanding development priority countries, its new policy and funding framework is going to need to be backed up by a much bigger budget.

Impact on expectations (click to enlarge)

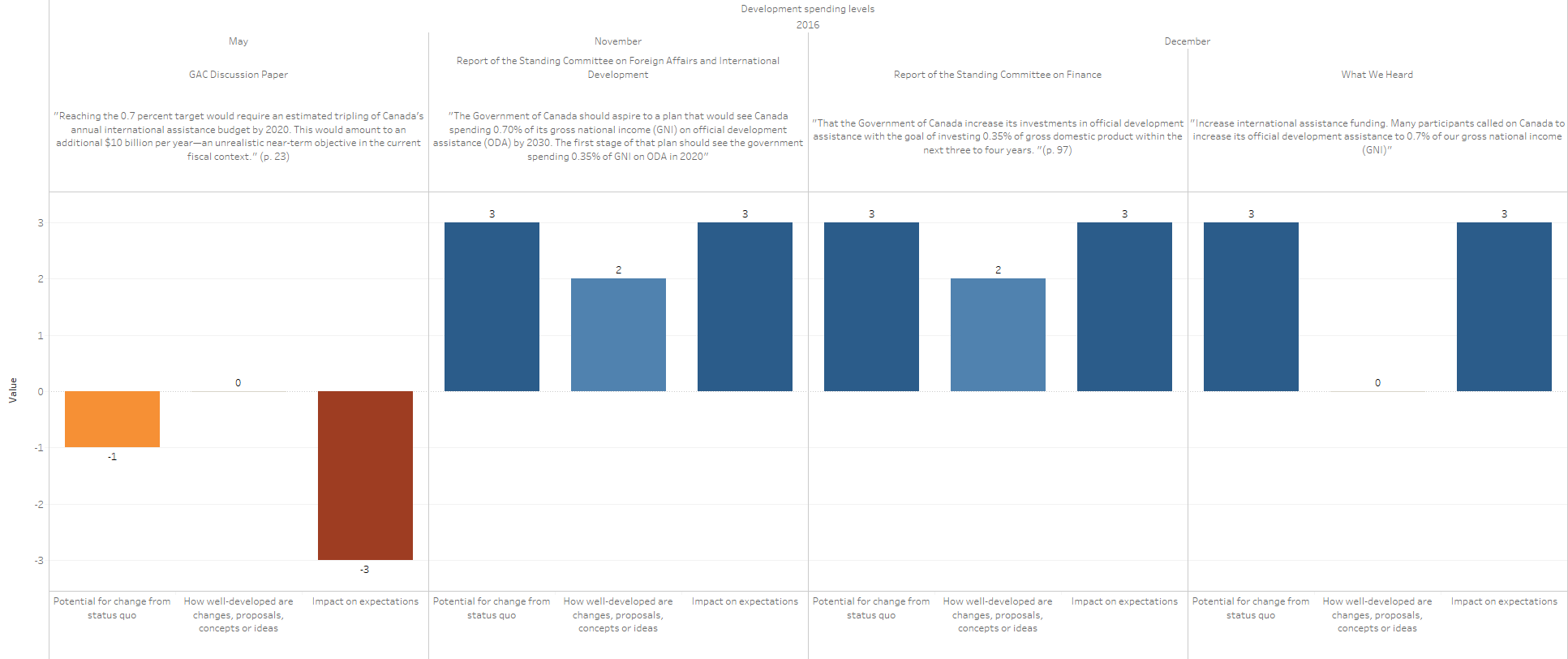

“Development spending levels”

The only area which receives a negative score in our analysis is “Development spending levels”. The trend in this issue area is particularly interesting.

The issue of Canada’s development spending level – which puts the current government on track for the “lowest commitment to international assistance of any Canadian government in the last half-century“, this includes the austerity package of the previous Conservative government – received no mention in either the Liberal party platform or the Mandate Letter.

Expectations were clearly ratcheted down further into the process. In the only reference made to spending levels the GAC discussion paper was explicit in its opposition to the 0.7% of ODA/GNI target, calling it “unrealistic in the current fiscal context” (perplexing given the new Liberal government undertook a significant fiscal expansion in its first budget and has only added to the same in every subsequent fiscal update).

Further into the process we find that the potential for change from the status quo and expectation surrounding change were elevated given both the Report of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development and the Standing Committee on Finance explicitly called on the government to set a time-bound plan for development spending increases with reference to the ODA/GNI ratio (essentially on a long-term path consistent with an ambition to achieve 0.7).

Canada has never spent close to 0.7% of GNI in ODA (the current level is 0.26, the highest ever achieved was 0.54). And similar recommendations by parliamentary committees have been made in the past (most recently by the Foreign Affairs committee in 2005).

Nevertheless, development spending levels appear in the middle of the pack among our issue areas in terms of expectations, while near the top in terms of potential for change from the status quo. Notwithstanding the fact that civil society and advocacy groups note the government has been trying to ratchet down expectations in the lead up to Budget 2017, this is a key area to watch in the upcoming budget.

Example of issue area coding: Expanding MNCH (click to enlarge)

Example of issue area coding: Development spending levels (click to enlarge)

Download

Download the datasheet (version: January 2017). MS Excel

Download Selected References (version: January 2017). MS Word

Recent Comments