By Aniket Bhushan and Lance Hadley

Published: Nov 30, 2020

How have Canadian exports performed during COVID19 and what is needed to ‘build back better’?

- Canadian export declines are off their April-May lows when they were down -40%.

- Our analysis of March-Sept 2020 vs. 2019 shows exports remain down approx. -19% during COVID.

- The pandemic has exposed structural vulnerabilities in Canada’s export performance. Two major factors stand out:

1) Diversification: despite significant policy effort Canadian exports remain the least diversified of any major economy.

- Lack of diversification extends beyond geography to areas like overseas investment, low participation of SMEs, and a highly concentrated product mix in volatile areas.

- Canadian exports are particularly vulnerable in a post-COVID global recovery that takes climate change seriously and further emphasizes ESG (environmental, social, governance factors).

- Canada’s exports to developing/emerging economies by contrast tend to be far more stable and diversified.

- During the 2008-09 global financial crisis, they fell about half as much as exports to rich countries. Similar trends are emerging during COVID.

- A key reason is the more diversified product mix that is underpinned by secular demand trends rooted in long-term development dynamics.

2) Deglobalization: these trends were already having a significant impact on Canada’s trade and investment prospects pre-COVID. We highlight China.

- Canadian exports to developing countries broke a long run of year on year growth and fell -5.2% in 2019 before the pandemic.

- The main driver was China’s retaliation over the Huawei VPs arrest.

- Canadian exports to China fell -16% in 2019.

- Not all trade and investment fell, however, pointing to China’s highly strategic approach, which we contrast with Canada’s incoherent response.

To build back better Canada needs to take fresh approach to trade with developing and emerging economies

- Canadian exports to developing countries tend to be faster growing but also more diversified and stable, especially during crises. This is likely to be the case again during COVID.

- Exports to a number of developing/emerging economies are up double digits. E.g. exports to China are up 10% and on track to exceed pre-Huawei 2018 highs.

- A post-COVID trade strategy update must further leverage this trend.

- GAC needs to be more decisive about linking trade, investment and development performance indicators and incentives.

- GAC’s development program and ODA budget can be used more creatively – for instance towards digital and services trade promotion, engagement in standard setting discussions on data ownership and usage, engagement with emerging regional trade blocs in Asia and Africa – towards mutual trade and long-term development benefit.

Breakdown of Export Performance During COVID

COVID19 hit trade dramatically and immediately, Canadian exports were no exception. Exports began their sharp decline in March and bottomed in April-May 2020 down approx. 40% year-on-year (YoY). While they have recovered somewhat since March, exports were still down approx. 6% in September.

If exports end the year around these levels in terms of declines, this will make 2020 the worst year for Canadian exports in two decades apart from the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

Canadian Exports and Imports during COVID (March-Sept 2020 vs March-Sept 2019, monthly)

Source: StatsCan CIMT via CIDP

These broad trends only reveal part of the picture. Canadian exports are particularly vulnerable, both due to their well-known lack of diversification, but also because they are highly concentrated in volatile areas.

During crises Canadian exports to advanced economies and supply-chain integrated trade partners, somewhat counterintuitively, tend to be more volatile compared to exports to developing and emerging economy partners. The key factor driving this trend is Canada’s export product mix.

- During the 2008-09 financial crisis exports to high income trade partners fell -27%

- Exports to developing/emerging economies fell far less -15%

- This divergence is driven by the export product mix

- In 2008-09, mineral fuel and oil exports fell from $132bn to $82bn; autos and auto parts exports, already down from $85bn in 2002 to $68bn in 2007, fell further to $38bn

- The oil price collapse in 2014-15 meant that mineral fuel exports fell again from $142bn to $82bn between 2014 and 2016 adding to volatility

These trends are dominant again during the COVID crisis. Data below on Canada’s monthly export product mix during COVID and performance relative to 2019 shows that:

- The same sectors (extractives and autos) are making an outsized contribution to export declines during COVID, e.g. mineral fuels (down -42%); autos/auto parts (down -35%)

- Only 4 sectors among the top 10 (precious metals, ores, wood, pharma) bucked the decline trend during COVID

- Canadian exports are down or flat in the case of 8 out of 10 of Canada’s top export destinations during COVID

- Our analysis of the March-Sept period, 2020 vs. 2019, indicates that exports are down approx. 19% during COVID

Export performance during COVID for Top 10 export areas (March-Sept 2020 vs March-Sept 2019)

Source: StatsCan CIMT via CIDP

Canadian Exports to Top 10 destinations during COVID (March-Sept 2020 vs March- Sept 2019)

Source: StatsCan CIMT via CIDP

Lack of Diversification takes Multiple Forms

Canada has the least diversified exports of any major advanced economy (as measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index). Lack of diversification extends beyond geographic concentration.

- 5 product areas make up over half of Canada’s exports (dominated by extractives like mineral fuels, oil; precious metals and stones)

- Over 90% of exports go to other rich countries (75% to the US alone); and 70% of exporters export to only one market (the US)

- Moreover, SME participation in exports is very low

- Only 12% of Canadian SMEs export at all (low compared to other OECD countries, especially given Canada’s definition of ‘SME’ is double that of European SMEs)

- Only 4% of Canadian SME sales are derived from exports

- The survival rate of Canadian exporters is low, only 30% of first-time exporters still export 4 years later

- Trade and investment often go together and Canadian FDI abroad is highly undiversified with less than 10% going to developing countries and only approx. 0.5% in Africa; the level of investment diversification decreases with income. In low income countries, 96% of Canadian investment is in the extractive sector

Along with changing the name and mandate of the trade ministry to explicitly include trade diversification, the Liberal government introduced a new export diversification strategy, backed the same with $1.1bn, and set specific targets in 2018. These included:

- Increasing exports by 50% by 2025

- Making cleantech exports one of the top 5 export sectors, tripling in value to $20bn annually by 2025

Export competitiveness in developing/emerging markets is vital to achieving these targets. Growth in Canadian exports to developing countries is a lot faster and more stable than to high income partners. This is largely down to a more diversified export mix underpinned by long-term secular demand trends.

Since 2002, Canadian exports to developing countries have grown every year except for the financial crisis. This long trend makes 2019 a major outlier. Canadian exports to developing countries fell -5.2% in 2019. A key reason for this is Canada’s contentious relationship with China.

Pre-Pandemic Deglobalization and the China Factor

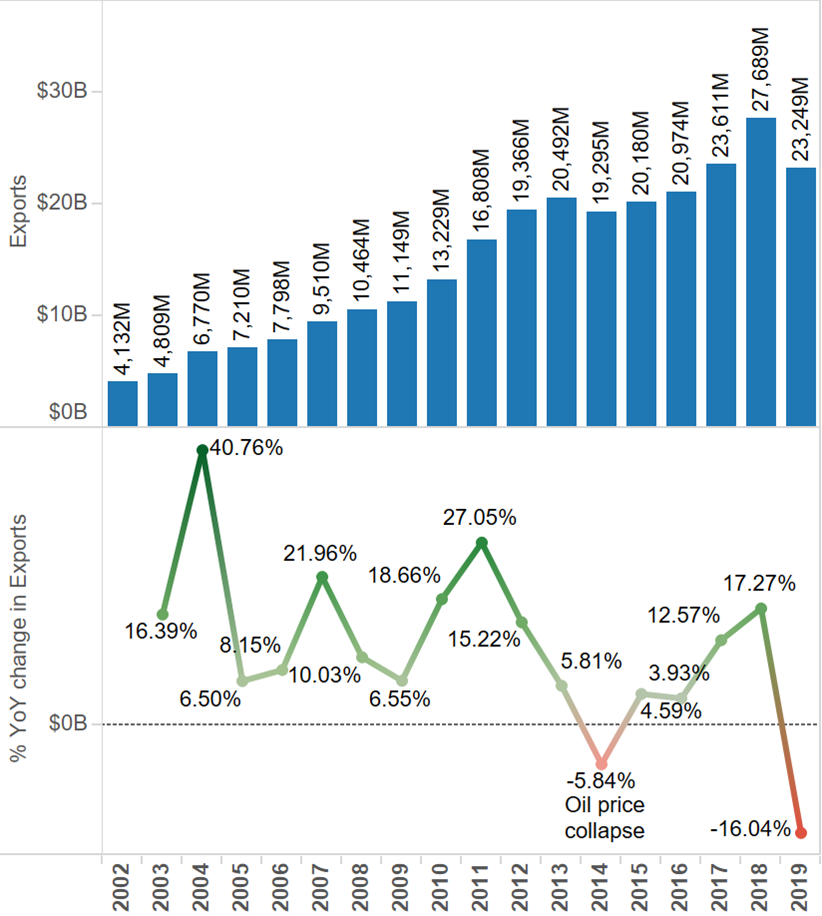

From a growth perspective, China is the most important market for Canadian exports. Exports to China are about the same size as Japan, Germany and South Korea combined. Canadian exports to China have been growing consistently and at a rate faster than overall export growth. Year on year export growth has been positive in all but one year over the last two decades including through the 2008-09 financial crisis.

This makes 2019 particularly noteworthy. Canadian exports to China fell dramatically in 2019, directly and immediately following the arrest of Huawei’s VP. Year on year exports to China fell -16% in 2019, by far the largest decline in two decades.

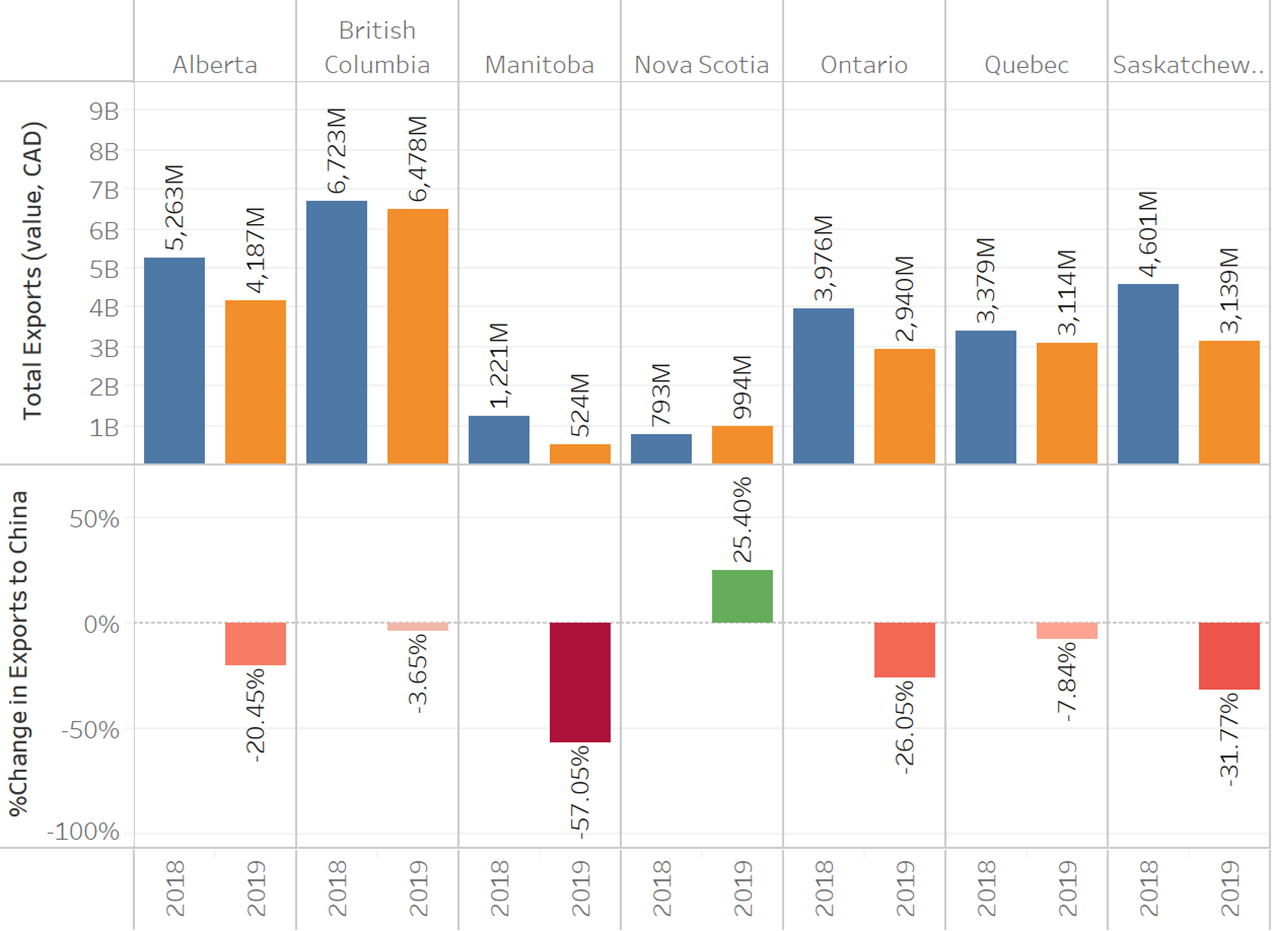

This decline masks significant variation and China’s highly strategic approach:

- Some provinces fared far worse: e.g. exports from Manitoba to China fell -57%, Saskatchewan fell -32%, Alberta -20%

- These trends were underpinned by extractives and agricultural exports that were relatively easy for China to substitute and buy from other partners

- One province, well-known for an export product that is not easy to substitute and has sky high demand in China, bucked the retaliation trend and points to strategic use of trade by China

- Nova Scotia’s exports to China, primarily seafood i.e. lobsters, were up 25%, practically the only export growth area post Huawei in 2019

- Chinese investment (FDI) in Canada declined precipitously both by value and no. of deals in 2019, but sector specific dynamics and strategic interests were again key factors. The only FDI recorded (up to Q3 2019) was in the rare earth sector in Manitoba, consistent with China’s long-term strategic priority of diversifying and securing supply

By contrast it has been difficult for Canada to respond to China with a coordinated coherent approach. Consider the following:

- Politicians across the spectrum – from Canada’s UN ambassador to the opposition foreign affairs critic – argue for a tougher stance, though none have articulated precise leverage points or how this approach would balance economic interests and safeguard against inevitable retaliation

- Canada has been quick to join ‘five eyes’ intelligence partners in condemning China on human rights (e.g. Hong Kong) and calling out other abuses (Uighur), but is yet to ban Huawei from 5G as others have

- Canadian sentiment toward China has turned negative significantly, and China is now seen more as a threat than opportunity, with a large segment of Canadians ready to stop doing business with China over human rights concerns

- Yet China is vital to Canadian businesses across the spectrum (take Jamieson Vitamins, which recently noted that while domestic sales increased 9%, international sales led by China, key to the company’s growth strategy, expanded 82%; or Canada Goose which recently reported that even as revenue declined during the pandemic, China had already returned to growth and sales there increased 30%)

Canada simply needs a more coherent approach to China. One that disentangles issue areas as opposed to conflating them further.

Long-Term Trend in Canadian Exports to China: Uninterrupted Growth Turned on a Dime Following Huawei

Source: StatsCan CIMT via CIDP

Pre-Pandemic Decline in Canadian Exports to China (2019 vs 2018, by province)

Source: StatsCan CIMT via CIDP

Relative Resilience of Exports to Developing and Emerging Economies

How have Canadian exports to developing/emerging economies fared during COVID? Our preliminary analysis indicates:

- Exports to several developing/emerging economies grew during COVID, even as overall exports declined significantly.

- Key again is China. Exports to China grew approx. 10% during COVID even as total exports remain down 19%. Part of reason may be the decline in 2019 as discussed, but even taking that into account, and despite COVID, exports are on track to exceed the pre-Huawei 2018 highs

- Export growth has been positive during COVID in a range of other developing countries, including Philippines, Colombia, Chile, and Peru

- Part of the reason again is the export product mix: agriculture and agri-food sectors make up over 42% of Canadian exports to developing countries

- Demand growth is secular and rooted in longer-term trends (demographics, urbanization, improving health and human development standards, growing middle class consumer bases)

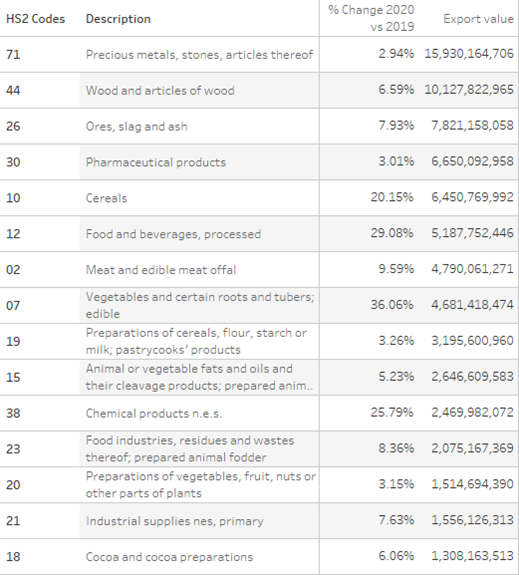

- A handful of export sectors standout in terms of relative resilience during COVID, these include vegetables, roots and tubers (up 36%), processed food and beverages (29%), cereals (20%), meats (10%), animal fats and oils (5%). These fit with the long-term demand pattern in developing countries

Canadian exports to select developing countries during COVID (March-Sept 2020 vs March- Sept 2019)

Source: StatsCan CIMT via CIDP

Export sectors (>$1bn) with growth during COVID (March-Sept 2020 vs March-Sept 2019)

Source: StatsCan CIMT via CIDP

Building Back Better on Trade

To build back better on trade our analysis of Canada’s export performance points to the following:

- It is likely during COVID Canadian exports to developing/emerging economies will prove to be more resilient when compared to more traditional partners. A key reason is the more diversified and less volatile product mix that is underpinned by stronger secular demand trends rooted in long-term development dynamics.

- Any post COVID trade strategy would do well to leverage this trend towards diversifying Canada’s trade footprint, which remains not only among the least diversified of any major economy but also one of the most exposed to short-term volatility and vulnerable in a potential global green recovery consistent with climate goals.

- Canada simply needs a more coherent and sensible approach to China. No trade strategy can go too far without addressing the China factor. China is by far the most important market for Canadian export growth and trade competitiveness. Exports to China have been resilient even during COVID and despite tensions. China also matters indirectly because it is among the most important trade partners for practically every Canadian export destination.

- Canada must be more decisive about trade, investment, and development strategy linkages. GAC in particular needs to clearly determine how far it is willing to go to make more strategic use of its development budget to showcase Canadian strengths in developing countries.

- At a minimum, coherence in country/regional strategies, investing in better understanding and forecasting demand dynamics, business and consumer profiles, ought to be priorities.

- Trade, investment, and development linkages can be incentivized by linking cross-sector performance indicators, in particular around engaging SME exporters. This could help address yet another facet of lack of diversification.

- Updated strategies on digital and services trade promotion; engagement in standard-setting discussions (especially around ownership and transfer of data); and with emerging regional trade blocs (e.g. in Asia and Africa) will be critical. Creative use of Canada’s development program including ODA budget could play a supportive role in each of these areas, towards mutual trade and long-term development benefit.

Recent Comments