by Robert Sauder

Published: February 21, 2017

This post is the second in our series on innovation in education.

Education is fundamentally important to sustainable development, with SDG4 (on education) often considered a “first among equals.” Happily, in recent years, there have been significant improvements in primary school participation rates in developing countries. Many of the key obstacles to access, such as school fees and lack of schools, have been significantly reduced.

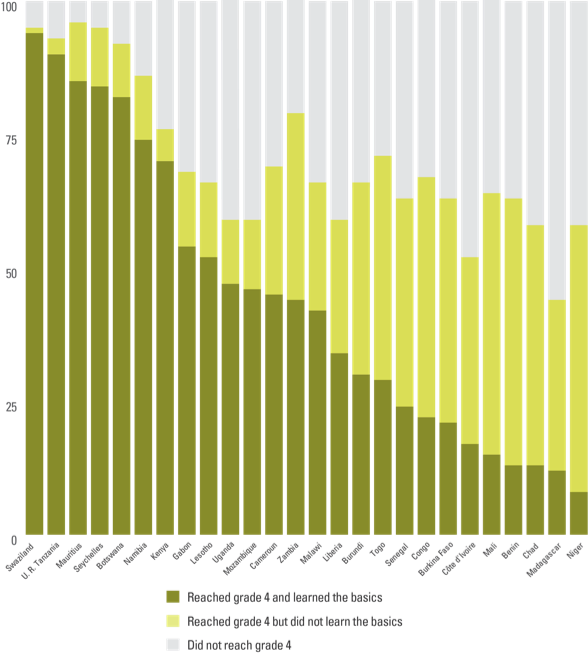

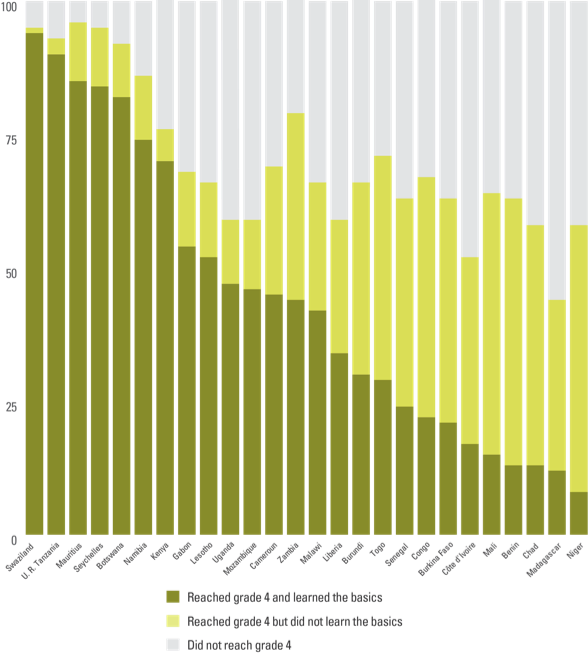

Data from UNICEF tell a positive story about increase in primary school participation:

Net enrollment rate and out-of school population among children of primary school age, 2000–2013

Source: UNICEF

Lurking behind this good news story is a much more negative one about declining quality.

The general quality of the schooling in the developing world is problematic and threatens the promise of development that education offers. Larger class sizes, together with outdated curricula, pedagogy and facilities, threaten to worsen the quality of schooling, which in many cases was weak to begin with. The resources available to schools for improving these conditions have dwindled, mostly due to abolition of school fees. Not only are many children still not in school in 2017, the quality of learning occurring for those who are is becoming questionable. Despite plenty of enthusiasm for access gains related to eliminating school fees, their long-term positive impact on learning is not clear.

Abolishment of school fees has had measurable and significant impacts on learning outcomes, persistence, and dropout rates. There has also been a flight of wealthier families’ children to private schools, which further exacerbates the inequities that drove the elimination of fees in the first place. A seven-country study of the impact of abolishing fees in Sub-Saharan Africa indicated serious concerns about educational quality.

In many instances, time in school does not mean learning.

An estimated one in four children in the developing world is unable to read. For girls in particular, the level of learning or literacy rates has hardly budged despite increase in years of school.

— Justin Sandefur, “Measuring the Quality of Girls’ Education Across the Developing World”, CGD. October 2016.

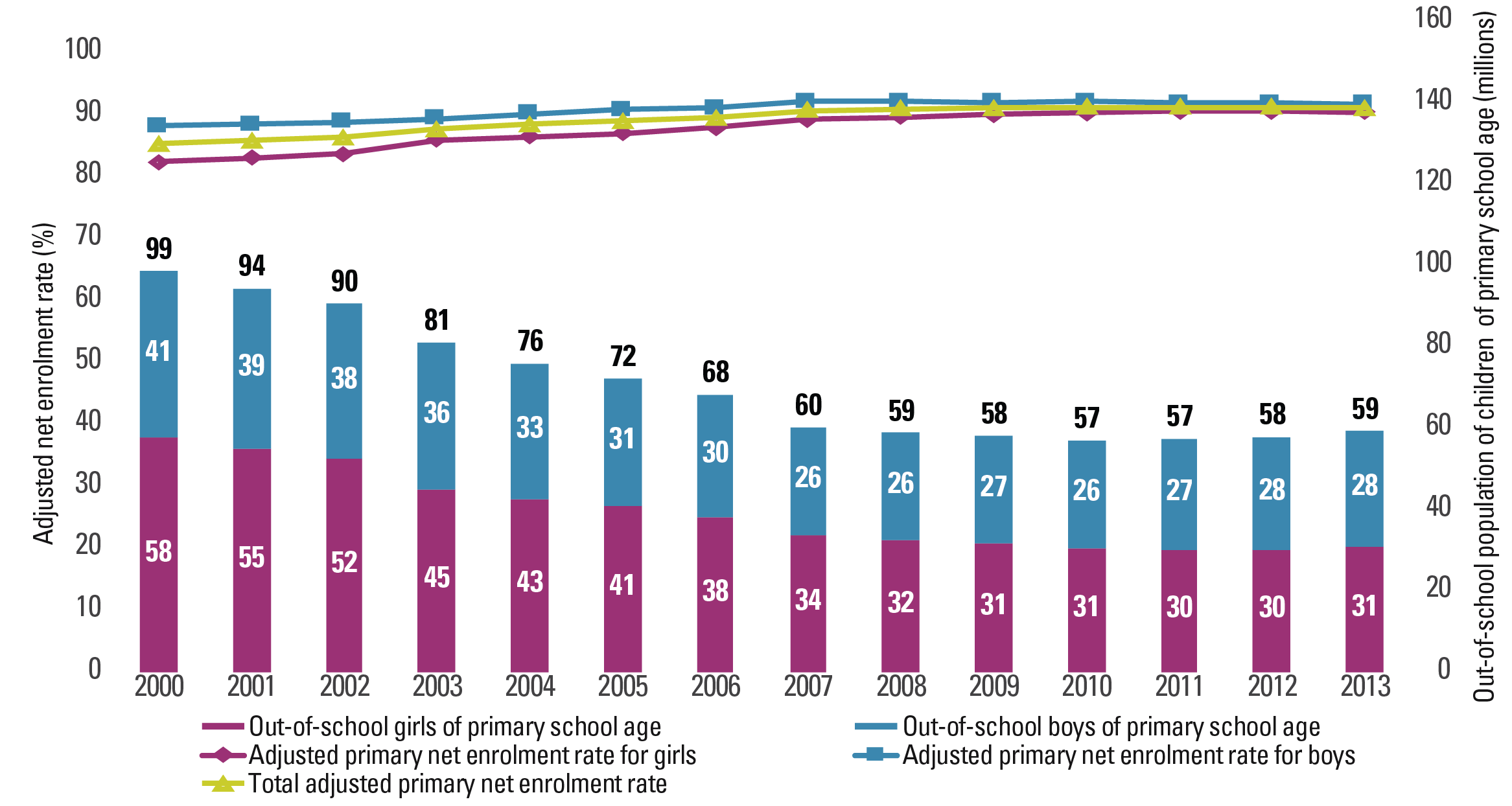

Overall, it is a grim picture. A large study of learning outcomes in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania found that, by Standard 7, a significant proportion of students had difficulty passing the reading and math skills for Standard 2. In West Africa, large numbers of pupils did not reach the “sufficient” threshold of learning in numeracy or literacy. Many sub-Saharan African countries face the double challenge of non-completion and low learning performance.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Completion and Learning Rates

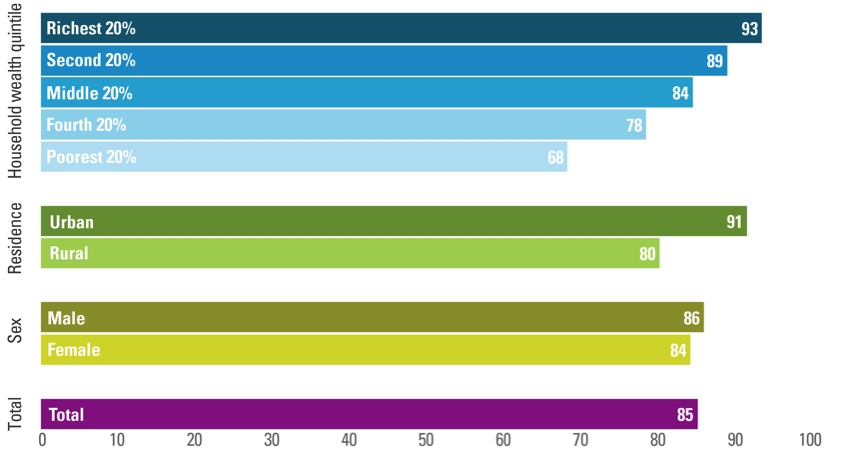

The responsiveness of developing country school systems tends to be poor especially toward low-income students and girls.

Primary School Net Attendance Rate (Percentage), by Household Wealth Quintile, Sex, and Residence, 2009–2014

Source: UNICEF

What do we actually mean by “quality”?

Is it the constituent components of the quality of the school system, or the ultimate outcomes of education, or both? The debate can be bewildering. Many discussions on educational quality descend into useful but dense explorations of definitions, metrics, key elements, and pedagogical models.

NORAD, for example, mentions six key elements, including teaching methods, educational content, the learning environment and school organization. It is obvious that these items are important, but a complex comparative analysis is required to understand what quality means and how you would compare the progress of one context to another.

There are significant differences among the levels of schooling and among state and non-states systems. Unfortunately, in such an analytical endeavour, you will immediately encounter confounding data and measurement gaps.

Shouldn’t we assess quality to a comparable standard?

There have been efforts to do wide scale and comparative assessments of learning, such as PISA, PASEC, PIRLS, and TIMSS. Aside from PASEC, a significant drawback of these international comparisons is that very few developing countries are included. TIMSS can tell you a lot about how developed countries have performed for the past 20 years in mathematics, but there are few developing countries involved aside from some growing middle powers like South Africa, Indonesia and Thailand. Even there, the performance was low. While there are serious questions about the PISA data and testing methods, these global pictures tend to show that, unsurprisingly, poor countries are doing poorly in education. Schools exist with very specific contexts and the outcomes of education will vary with those contexts. While these international assessments provide some insights, there is need for a framework to understand quality, which can fit a variety of contexts.

How can we understand quality in a simple and useful way?

It is difficult to fairly and consistently evaluate what all these elements add up to in a given school system. There are significant differences among learning assessment systems in different countries and an appalling lack of useful data. The presence of various high quality elements is no guarantee of success.

What is needed is simple and communicable understanding of quality.

In a simple sense, high quality schooling is that which meets the learning needs of students and leads them to a successful completion of the curriculum where they live. Obviously, if students drop out or do not pass, the quality of education is low.

High retention and pass rates imply a large proportion of what is generally denoted by the concept of quality. The proposition is that, in a school system of reasonable quality, nearly all students would enter school and be retained until they passed the basic primary school leaver standard. The language of instruction, pedagogy, teaching methods and additional supports—for example, remedial education—would be diverse and effective enough to ensure most students got through.

In effective school systems, systematic interventions would be deployed to mitigate large groups of students from dropping out and/or failing their exams. If there were large-scale non-participation of particular groups of children (for instance, children who must work to support their families), school hours and facilities can be adjusted to permit part-time work. There are many efforts underway to build equivalent or parallel schooling for out of school children, for example, UNESCO’s Strengthening Education for Out of School Children.

Quality means attracting, retaining and graduating

Interventions and innovations that tackle the underlying challenge of attracting, retaining and graduating the vast majority of children in a country need more exposure and support. These solutions need to focus on real blockages to student learning. Fortunately, there is a growing body of evidence on potential solutions in teacher training, curriculum reform, school management, ECD and parental involvement. For instance, a review of impact evaluations found that interventions that matched teaching to student’s learning showed the greatest impact on learning outcomes.

Untangling the effects of external challenges, such as a frail economy, patriarchal social relations, or government corruption, on educational quality is important. It should not distract us from the pressing need to direct more resources to education and try more innovations that ensure all children come to school, stay in school, and actually graduate from school.

Recent Comments