by Robert Sauder

Published: June 22, 2017

Education remains a major topic of interest in development and several major reports on recent trends and financing have deepened this interest. CIDP has highlighted several issues in education recently, including reform challenges and quality concerns. Globally, there is a movement to frame education as pivotal to the feminist development policy. The title of a recent report by the organization, ONE, says it clearly: “Poverty is Sexist: why educating every girl is good for everyone”. Canada has signaled an interest in a feminist approach as well.

The Global Partnership for Education (GPE), to which Canada has contributed nearly $192 million (USD) has been advocating strongly for increased donor support to education. The next replenishment cycle of the GPE is due in late 2017. In the health sector, Canada has shown significant leadership with the substantial replenishment of the Global Fund announced in Montreal last September. Those in the education sector have been advocating for a similar large increase in donor contributions.

It is therefore appropriate to do a review of the trends of Canada’s support for education. All data, unless otherwise noted, are derived from OECD-DAC statistics. All figures are in USD.

Canadian support to education has declined over the past decade

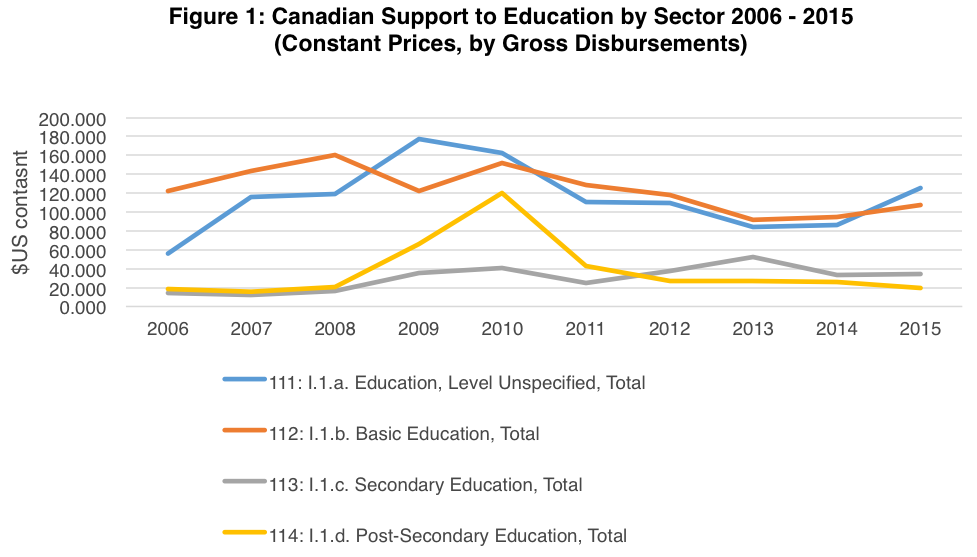

Figure 1 below shows the 10 year trend for Canadian official development assistance (ODA) for various education sectors. While there have been spikes of support, the overall trend is downwards or flat. The spending under the marker “Education, unspecified” notes four possible activities: education policy and administration, facilities and training, teacher training, and research. This area of spending is the only one that shows a significant upwards trend recently.

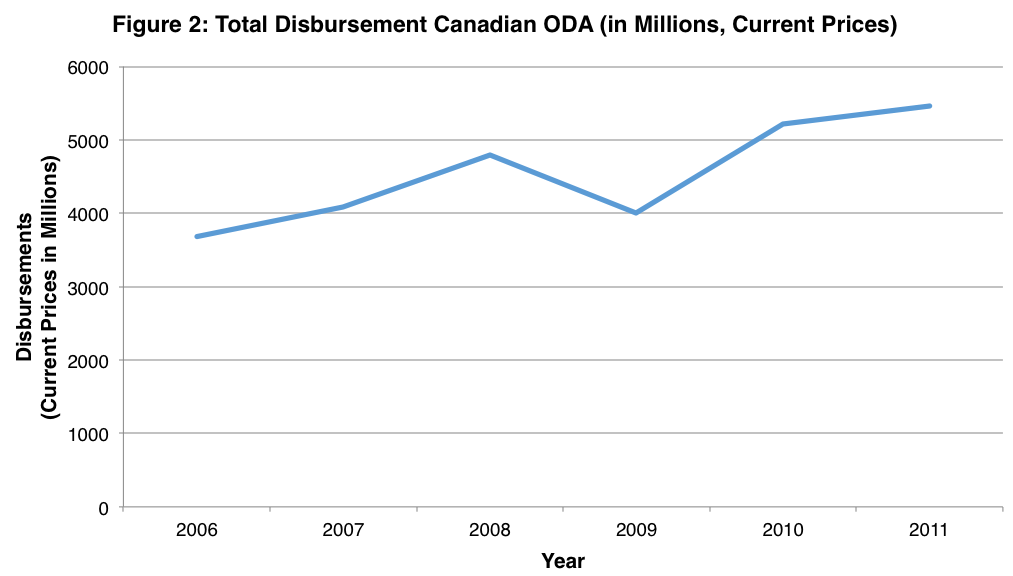

Spikes in support of education can be observed around 2009-10, followed by a downward trend thereafter. This follows the general pattern of decline in Canadian ODA, which peaked in the years 2010-12. Figure 2 shows this trend line of a spike in Canadian ODA followed by a plateau till 2015. Although ODA increased in 2010-12, the decline in education funding pre-dated this and did not appear to get a boost when ODA rose.

Canadian aid to education has not been very stable

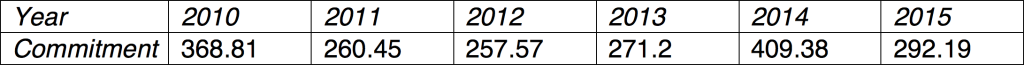

Figure 3 indicates a somewhat variable picture for education funding over the past five years. 2014, for instance, showed increase of over $137 million from 2013, but by 2015 it declined again. The underlying data show that much of this increase was derived from increased spending in education (unspecified level) and basic education. In 2015, spending on basic education dropped significantly while education (unspecified level) held fairly constant.

Canada has not followed DAC trends

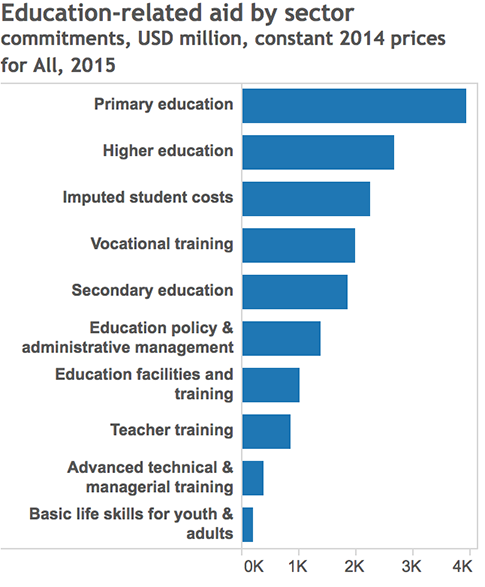

An OECD 2016 report on donor support for education (2009-14) provides comparative data on spending on education. The report indicates that among sub-sectors for education for all DAC donors, post-secondary education received the largest percentage of aid (34%) followed by basic education (26%), secondary education (15%) education policy and administration (15%) and education facilities, training and research (10%). Canada is atypical of this breakdown with significantly more spent on education administration and basic education than on other sectors.

In terms of gender equality focused aid to education, in 2013-14 Canada spent $219.5 (annual average commitments). This consisted of $142.9 million (gender as a principal objective) and $76.6 (significant objective) which represented about 66% of total aid to education. The average percentage for DAC donors for gender equality focused aid to education was 57%.

Figure 4 shows Canadian education aid by sector in 2015. The line, “Imputed student costs,” indicates funds spent to subsidize education costs borne by developing country governments. This may come through a variety of channels, including bilateral and multilateral. Three sub-sectors, facilities, policy and administration, and teacher training, together make up a substantial portion of the spending.

Canada supports education through multilateral institutions and the OCED calculates imputed support by individual donors. Canada has provided a consistent level of multilateral support over the last five years, with the average imputed budget hovering above $50 million. The largest component of that support has been to IDA. In 2015, in its overall spending of $54.74 million, Canada contributed to IDA $37 million. Since these supports are low interest loans to low-income countries, much of the funding goes to support education infrastructure, such as building or upgrading schools.

Canadian funding of education needs a strategy

Aid to education by Canada has not been a high priority in recent years, especially relative to signature programs such as maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH). There is considerable variation in spending on education sub-sectors. This may be the result of particular program opportunities that have arisen from time to time or perhaps individual ministerial preferences. Canada has prioritized education administration and basic education as well as gender. The current level of support for secondary education is low.

The data in this review reflect programming done under the previous Conservative government. Changes in Canada’s approach to education may be forthcoming in light of the new feminist international assistance policy and framework. As the replenishment of GPE looms and the discussion intensifies about providing more opportunities for women and girls, Canada faces some challenging questions.

How should Canada use education prioritize women and girls? What is the right balance among sub sectors? Are loans (for example, through IDA) more effective than cash transfers or teacher training? What are the relative impacts of funding multilateral organizations like GPE compared to bilateral programs? If there are no places for girls in secondary schools, will massive support for girls in basic education result in better outcomes?

Recent Comments