by Robert Sauder and Emma Anderson

Published: March 20, 2017

Canada’s international development policy has been under review since May 2016. The Prime Minister has been vocal on the importance of a “feminist” approach to public policy and the Minister of International Development, Marie-Claude Bibeau, has echoed the refrain. If Canada has an ambition to have feminist approach to its new development policy, it is useful to examine what that has meant for other donors. Our review indicates there are common elements:

- Top policy prioritization for gender

- Gender action plans

- Coherence with related gender policies, including UN Resolution 1325

- Additional efforts to increase impact on gender

- Substantial budgets aimed at gender

On these elements, how does Canada rank compared to other donors? In terms of comparator countries, we consider a sample of those which are similar in size to Canada or which have a reputation for gender programming. This includes Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, the UK and Australia.

What is the level of policy prioritization for gender?

Among the selected donors, Australia and Sweden have most extensively articulated gender as a policy priority in key documents. Sweden has an explicit “feminist” development policy with six inter-connected areas of activity with specific goals and plans to achieve them. The Netherlands does not identify gender a policy priority per se, although sexual and reproductive rights is named as one of its four priorities. Gender is not among the UK’s or Norway’s top priorities. For Canada currently, gender is considered a “cross-cutting theme,” not a policy priority.

Is there an action plan for gender?

All six donors reviewed have gender strategies in place. These typically include a requirement to do gender analysis as part of the design of development projects. Also common are references to need to address the underlying causes of gender bias, to focus on women’s rights, to reduce violence against women, to empower women economically, and to boost programming in sexual and reproductive health. The involvement of men and boys in social change is often cited as important. The Norwegian action plan might be considered typical. Canada’s gender analysis framework shows many commonalities with most donors’ approaches to gender.

What is the level of coherence with other policies related to gender?

Only Sweden and Australia have explicitly comprehensive feminist foreign policies. Australia’s policy identifies four key commitments, including integrating gender equality and empowerment into foreign policy, trade, economic diplomacy, development programs, and corporate and administrative practices. Norway has a gender action plan that identifies links to other policy domains. For Canada, the Netherlands, and the UK, gender equality and women’s empowerment remains a policy focus and an area of substantial programming, but gender is not framed as a comprehensive approach.

In terms of other policy frameworks, such as trade or diplomacy, coherence is often elusive, both hard to do, and to evaluate. While Sweden is seen as a leader in feminist policy, there have been critiques about its impact. Sweden took a well-publicized stand on not selling arms to Saudi Arabia, which has a poor human rights record, but in the end, Sweden had to soften its stance. Canada has substantial expertise on gender in its Ministry for the Status of Women and recently signaled convergence with international efforts on gender development at the UN.

For many donors, policy coherence on gender requires substantial efforts in relation to UN Security Council Resolution 1325. Signatory states have action plans related to direct and underlying causes of gender-related bias and abuse. Many of the programs and objectives of these plans closely align with development objectives. All six donors that have been reviewed have detailed action plans on resolution 1325. A typical one would be the Dutch comprehensive action plan.

Are there special efforts to ensure gender impacts?

Gender budgets, policy ambitions, and gender strategies are not considered enough by some donors to be sufficient. There are always the dangers of path dependency, façade conformity, and tokenism. Donors tend to carry on as they have before and there is the risk that gender is simply a ‘box-ticking’ exercise. Canada’s Minister Bibeau has shown awareness of this issue.

A number of donors take additional steps to ensure greater gender impact. For instance, Australia requires that: “More than 80 per cent of investments, regardless of their objectives, will effectively address gender issues in their implementation”. Indications are that Australia is making progress towards this benchmark, having reached the 78% mark in 2014-15. Another example is the UK’s International Development Gender Equality Act (2014). The Act requires the measurement of the impact of its overseas aid on reducing gender inequality. An 2015 evaluation report of the Act lauded Britain as a leader in the area. In Canada all development project proposals require a gender specialist sign-off.

Some donors, for example Norway , have undertaken reviews of their gender related programs and instituted changes to improve their effectiveness. There have also been updates to several donors’ actions plans for resolution 1325. Australia has undertaken additional efforts, for example, appointing an Ambassador for Women and Girls to advocate on gender issues. In 2015 the Australian foreign ministry announced a new internal ‘women in leadership’ strategy, which included change champions, recruitment targets, and performance objectives.

What are the budgets dedicated to gender?

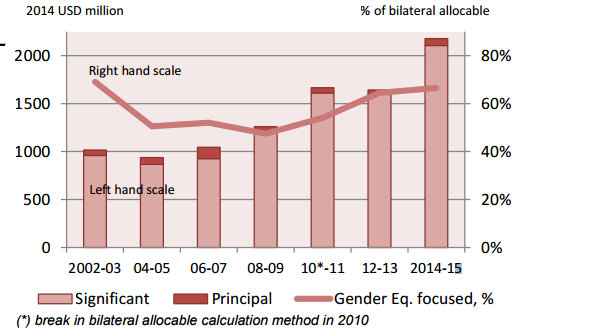

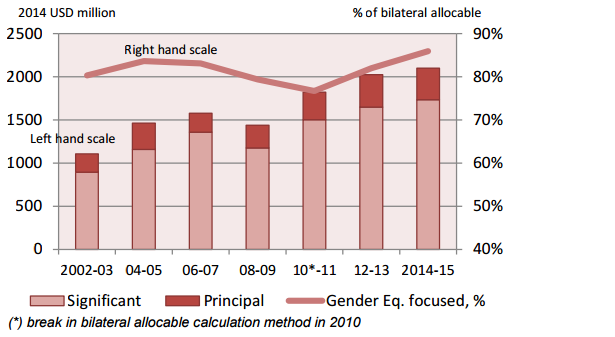

A review of the budgets among the six donors reveals significant variation in the proportion of spending devoted to gender. Table 1 (below) compares the proportion of ODA across donor gender budgets directed to gender equality and women’s empowerment. For our purposes, aid to gender equality or women’s empowerment is understood using the OECD-DAC’s definition of aid for which gender equality is an explicit, or “principal” objective, of the activity. All data reported is taken from the OECD-DAC’s 2017 “Aid in Support of Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment, Donor Charts” publication, and measures donor commitments.

The Netherlands, the UK and Sweden lead the group in terms of the proportion of aid to gender and women’s empowerment, committing 15.3%, 15% and 14.8% to gender-focused programming, respectively. While 10.4% of Norway’s bilateral allocable commitments reflect a principal focus on gender, Australia and Canada report a mere 5.5% and 2.2% of bilateral allocable commitments as principally focused on gender programs. Figure 2 below shows Canada as compared to Sweden on the proportions of principal vs. significant.

Table 1: Aid for Gender and Women’s Empowerment, 2014-15 average

| Country | Aid for gender and women’s empowerment (principal only) $USD million 2014 | Aid for gender and women’s empowerment (principal only) as % of total bilateral allocable | Aid to women’s rights CSOs as a % of total gender focused aid* |

| Australia | 175 | 5.5% | 24% |

| Canada | 72 | 2.2% | 33% |

| The Netherlands | 522 | 15.3% | 50% |

| Norway | 396 | 10.4% | 47% |

| Sweden | 367 | 14.8% | 17% |

| United Kingdom | 1,200 | 15% | 17% |

* Source: OECD, Donor support to southern women’s rights organizations, November 2016

Figure 2: Canada (on the left) vs. Sweden: Spending on Gender Equality

Source: OECD, Aid in Support of Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment, March 2017

It is important to note that our analysis suggests there are data issues and inconsistencies within the OECD-DAC source that significantly affect figures for Canada. For example, while the DAC data suggest major (over 10 fold) changes in gender budgets, this is not corroborated by Canadian data sources. Moreover, Canadian sources, using the policy marker approach (level 3), suggest Canada’s gender focus as compared to the DAC definition of “principal objective” is even lower—approx. CAD$47.7 million (2014-15), or less than 1.5% of total bilaterally allocable and assessed aid. Over the past decade, it has ranged between 1% and 3%. In other words, far lower than OECD-DAC data suggest.

We caution that the OECD-DAC source is potentially misleading as far as Canada’s gender focus is concerned. However, in order make comparisons to other donors, we are forced to rely upon it. There are indications that Canada’s gender budgets may be even lower, but further analysis is needed to reach clear conclusions.

Conclusion

This review has considered the policy norms and typical components that a sample of donors deploy in the name of a feminist development policy. The summary table below indicates Canada has some of the common elements of a feminist development policy.

| Donor | Top policy prioritization | Gender action plan | Policy coherence with other policy domains | Action plan for resolution 1335 | Additional efforts | Substantial budget |

| Sweden | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| UK | x | x | x | x | ||

| Netherlands | x | x | x | |||

| Norway | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Australia | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Canada | x | x | x |

There are many budgeting options available to donors, ranging from funding for sectors of high relevance for women, such as SRHR, or local women’s right organizations to funding projects that only have gender as a collateral benefit. Although the DAC codes of principle vs. significant objective are assigned after the fact, it seems logical that a more feminist model would have a greater proportion of projects with gender as a principle objective. Canada currently ranks lowest as compared to the other donors reviewed. The announcement on International Women’s Day of substantial funding ($650 million over three years) for SRHR may boost Canada’s gender spending with a principle objective.

As a general model to emulate, in terms of budget, policy, and strategy, Sweden is a clear leader. However, several other donors strongly prioritize gender and are making efforts to improve their performance in this area. The signals from the Canadian international assistance review and the government more generally, are that gender will be promoted upwards from being a ‘cross-cutting’ policy priority. If Canada wants to move to the front rank of feminist policy, it can draw lessons from other donors, for example the UK’s Gender Equality Act, Sweden’s highly integrated policy framework, and Australia’s targeting strategy.

Recent Comments