by David Carment

Published: December 15, 2015

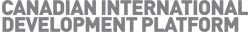

Despite being recipients of some of the largest diaspora remittance flows in proportion to their overall economy, twenty of the most fragile states have remained extremely fragile for over ten years. Estimates of fragile states vary.

According to data from the Country Indicators for Foreign Policy (www.carleton.ca/cifp) project, more than half of the forty fragile states classified as fragile in 1980 were still considered fragile in 2014. They are stuck in a “fragility trap”. To the extent that remittances can, in theory, help lift people out of poverty and promote development, one should observe a decline in state fragility in those countries that receive significant amounts of remittances. Yet this is not always the case.

Why do some states remain poor and stuck in a “fragility trap” despite the attention they receive from their diaspora, including heavy remittance flows? In answering this question I argue that fragile states exhibit, by definition, poor policy environments in which resources are improperly allocated toward productive ends. Positive and effective diaspora engagement depends on functional trade relations, foreign direct investment, functional property rights, effective development assistance good governance and effectively channeled remittances.

Much of the research on remittances focuses on middle-income countries; where positive findings show they enhance capital access and business creation and increase economic openness. But remittances may be less effective in fragile states. To illustrate this point consider Tajikistan, where remittances account for 41% of GDP. For Haiti and Yemen, two other fragile states, the proportions are 20% and 10% respectively.

A problem occurs in these countries when increasing fragility motivates even more remittances, leading to greater dependence on remittances, migration out flows, a hollowing out of the economy and low growth due to a lack of investment opportunities. Dependence on remittances calls into question whether a safe exit from fragility might be expected where remittances are so extensive.

Consider the volatility the Russian ruble crisis is inflicting on those fragile states along Russia’s border which are dependent on the billions of dollars sent home by migrant workers. The negative effects are twofold. The ruble’s drop in value means that migrants are discouraged from staying in Russia, putting an even greater burden on homeland economies when they return. Regionally, the remittance drop in 2015 could amount to more than a $10bn loss for 9 countries that heavily rely on remittances from Russia.

Research has found that the poverty reducing impacts of diaspora activity is largely dependent on the priorities and strategies of home country governments; meaning that effective policy environments matter. To a large extent, positive and effective diaspora engagement depends on the existence of sound government policy designed to enable and encourage diaspora activities in areas of primary importance to the country. When neglected or poorly conceived, government policy can represent a significant barrier to diaspora involvement; in extreme cases, such barriers can provoke opposition to the government among diaspora populations. Further strategies that might work for middle income countries are less effective in fragile states where poor macro-economic conditions, underdeveloped markets, corruption and poor investment climate often threaten the success of such policies

Future research on diaspora and fragility should:

Afghanistan is a prime example of the failure of governance to capitalize on massive donor resource flows to begin to move out of the the fragile state category. Billions have been spent over the past decade, much of which wound up in donor countries or was siphoned off by predatory elites. A sad story, hopefully a few useful lessons are being learned and the next generation of leaders will do a better job.