by Kateryna Sherysheva

Published: November 15, 2015

Canada, like other donors, has committed to delivering humanitarian assistance solely based on need. In 2003, Canada endorsed the Principles and Good Practices of Humanitarian Donorship, which include the principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality, and independence. Despite the clear commitments, scholars and auditors have raised concerns that there are inequalities between humanitarian relief distributions.

For example, the Office of the Auditor General conducted a performance audit of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development’s (DFATD’s) response to international humanitarian crises. The audit concluded that it was often unclear how DFATD determined the amount of funding to provide. One decision document noted that DFATD typically responds by funding 3% to 5% of an appeal. However, other documents show that DFATD provided approximately 2.5% of the requirements for the East Africa drought for 2011, while disbursing 7.5% of funding requirements in response to the Philippines Typhoon Haiyan in 2013.

If so, humanitarian distributions could be linked to strategic considerations rather than based solely on need, which is reflected through the number of casualties and the number of people affected (experiencing actual or imminent threat to life, health, basic subsistence and/or security).

Summary of the quantitative analysis

Using a sample of 674 natural disasters occurring between 1999 and 2013 in developing countries, I conducted a quantitative large-N study to assess whether Canada’s humanitarian aid reflects the humanitarian principles it is supported by. The need variables of the number of casualties and the number of people affected were taken from the EM-DAT Database while funding data was taken from OCHA FTS. The empirical model controls for recipient country’s capacity to respond to disasters in addition to variables that could be interpreted as strategic factors. The model assesses both Canada’s decision of whether or not to provide relief in a disaster and if yes, the amount to provide.

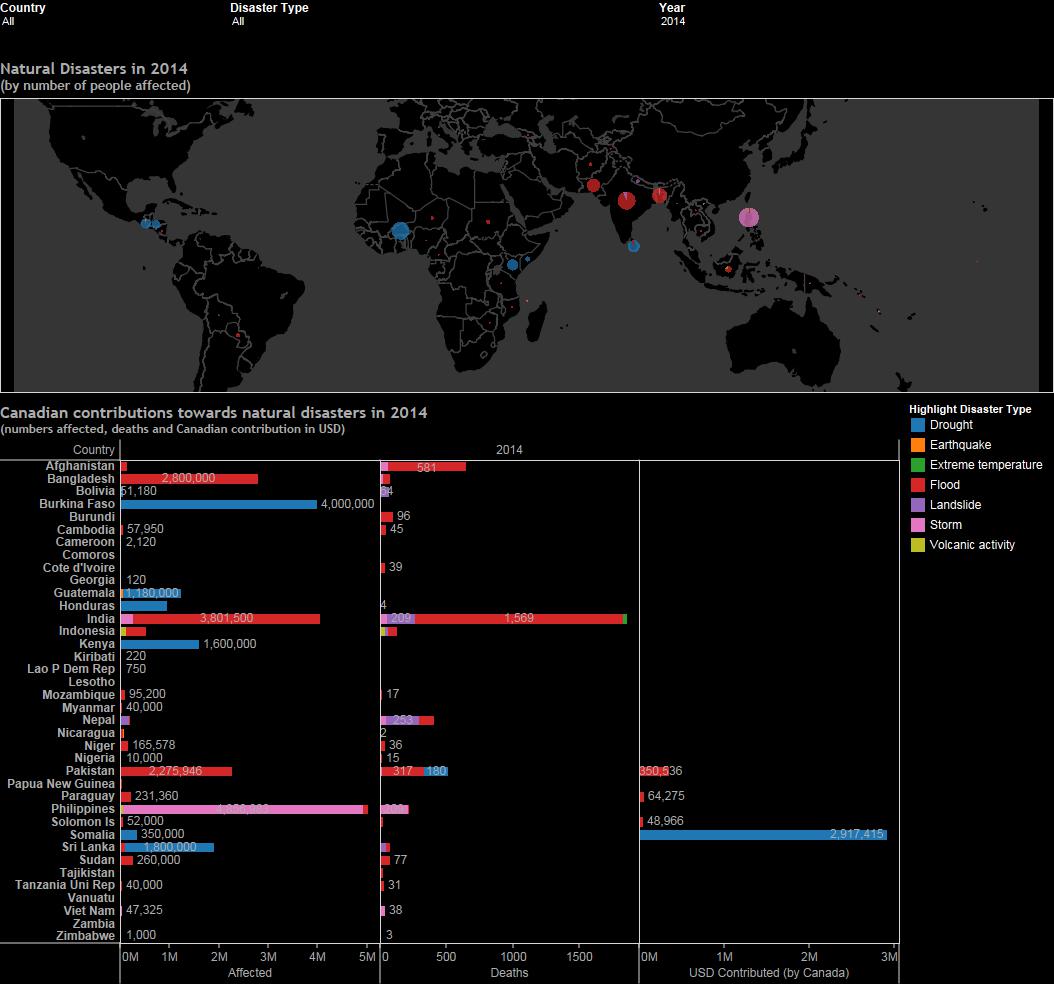

Figure 1. Natural Disasters and Canadian Humanitarian Relief Allocations (click here or the image to interact with the data)

The study found that overall, Canada provides relief both based on need and strategic considerations. For example, while Canada is more likely to provide relief to countries that have had more casualties and more people affected, it also provides more to countries that are geographically closer to Canada, to which Canada provides fewer exports, and that are more democratic. It should be noted that Canada responds to disasters for which there has been a call for international assistance, while the study included disasters that have met a threshold of deaths and casualties including those that may not have had a formal appeal. However, all the disasters examined in the amount decision were responses to an appeal.

Interestingly, the number of people affected by a crisis did not appear statistically significant. The study also found that Canada provides more relief to countries that are members of the Commonwealth and that receive fewer Canadian exports. This could suggest that humanitarian relief is used to establish a partnership for future trade relations.

It should be noted that the study does not capture core funding that Canada provides to international organizations, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross. The study only looks at earmarked funding which tracks Canada’s decision making of allocations between disasters.

Policy Recommendation

While DFATD already subscribes to the international policy framework of providing humanitarian relief based on need, there remains room to strengthen the implementation of this policy in practice. Developing a strategic plan for implementation could be a first step towards ensuring that humanitarian relief is allocated based solely on need. Ideally, the plan should meet three basic criteria.

First, any strategic plan should be comprehensive and cover all humanitarian responses across the Government of Canada. Seeing as many government departments are involved in providing humanitarian relief, having a strategy that considers the whole-of-government response would reduce the risk of competing objectives or duplication of effort.

Second, the strategic plan should be publicly available to promote transparency, and allow for predictable humanitarian programming and advocacy. Making the plan open to the public would also foster structured discussions with partners, including Canadian civil society organization, multilateral institutions, parliament, scholars, and Canadian citizens.

Thirdly, and most importantly, the strategic plan should have clear, measureable standards and objectives. Having measurable objectives is necessary for future monitoring and evaluations, the results of which could be useful in driving government accountability.

Similarly, using clear and measurable standards for relief allocation could ensure an equal response to emergencies.

The numbers and/or percentages would need to be determined via a thorough analysis of the maximum amount Canada would be able to contribute based on available funds.

Additionally, focusing on disaster risk reduction and building resilience to disasters in developing countries will be an important step for mitigating the impact of disasters in the long run. Seeing as those who are already vulnerable are most affected by disasters, working to build country capacity to detect disasters and protect people from the worst impacts provides a long-term sustainable solution to saving lives and minimizing need in disaster responses.

Developing a comprehensive and publicly available Humanitarian Relief Strategy that has clear, measurable objectives, and that links need and monetary allocations remains an ongoing challenge to ensure that Canada remains accountable to its commitments.

Recent Comments