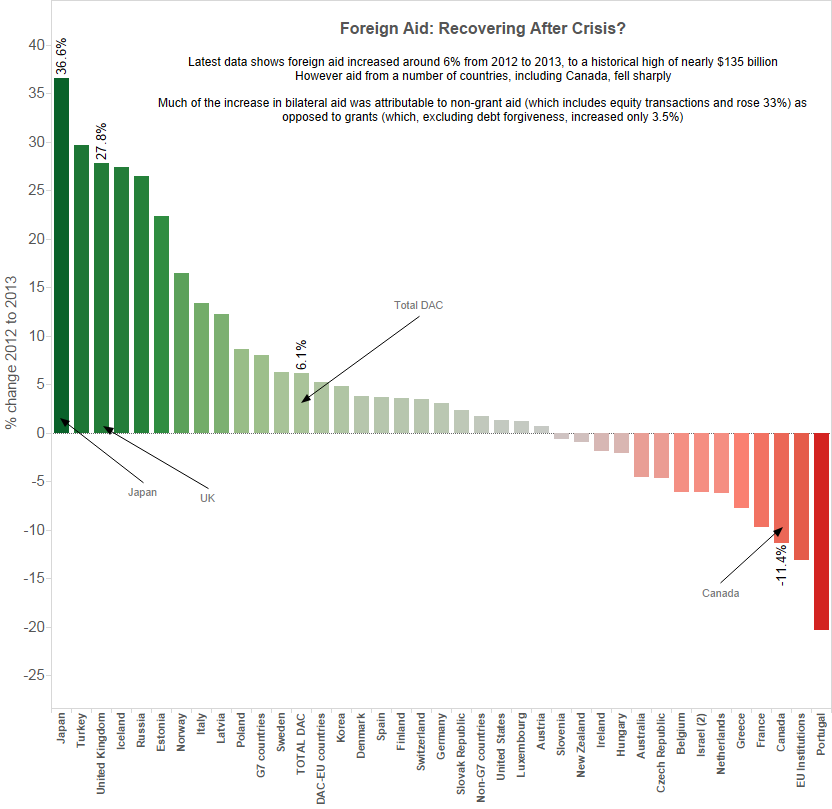

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) has released their preliminary data on foreign aid spending for 2013. The data show an increase in aid of around 6% in 2013 compared to 2012. At nearly $135 billion, net foreign aid reached an all-time high in 2013.

The main reason for the increase is that a number of large donor countries significantly increased aid spending to meet predetermined goals. The UK’s foreign aid, for example, rose nearly 28%, to meet its goal of reaching the 0.7% of GNI UN target.

We update our analysis of year-on-year trends through this post. Follow this page for further analysis as we update Canadian aid data.

Canada among the DAC

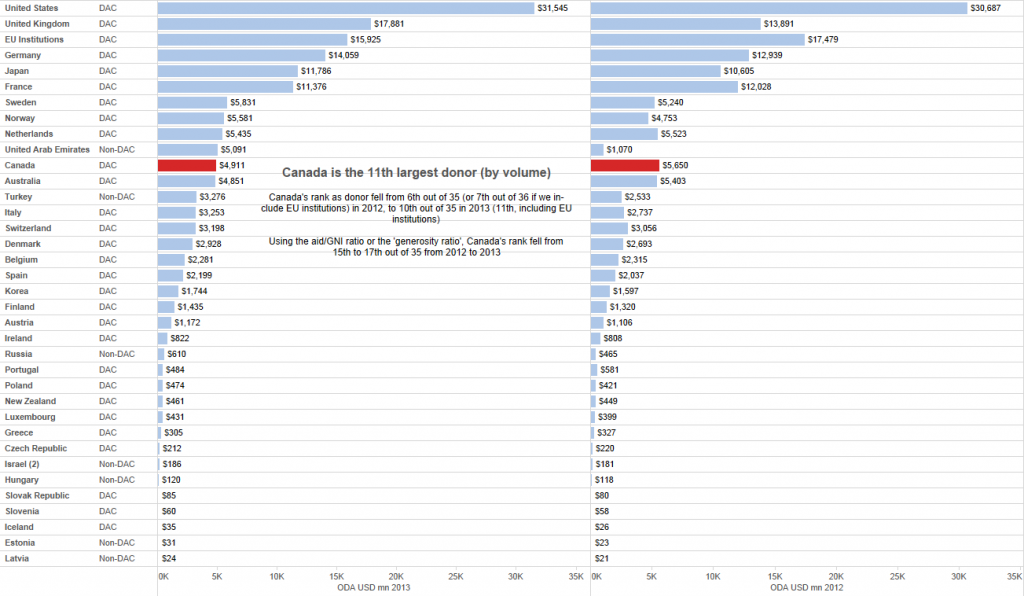

Canada’s aid fell significantly (-11.4%). Canada’s rank as an aid donor (in volume terms) fell from 6th (or 7th including EU institutions) to 10th (11th including EU institutions). Similarly, Canada’s rank in terms of the generosity index (or the aid to gross national income ratio) also fell from 15th to 17th (out of 35).

Canada’s aid-GNI ratio at 0.27% came in well below the DAC average, the average country effort and the UN target of 0.7% (which has now been achieved by 5 OECD-DAC countries, 6 including the UAE which saw an exceptional rise due to its aid to Egypt). OECD-DAC data (in US$) indicates a decline in real terms of $739 million in Canadian aid.

Two explanations are given for Canada’s aid decline: exceptional payments for climate change and debt relief in the previous year; and budget cuts.

Data available at this preliminary stage does not allow for greater analysis of these explanations.

However we can shed some light on recent trends. Canada’s climate finance commitment over three fiscal years, 2010-11 to 2012-13, totals $1.2 billion. The commitments were spaced nearly evenly across the three years ($385.8 mn; $382.5 mn and $425.1 mn approximately). So it is unclear what the exceptional payments are at this stage.

While these are new and additional resources, concerns have been raised about their impact on aid to other areas and the balance between loans and grants (loans account for a significant share of Canada’s climate financing).

The only major recipient of Canada’s debt relief in 2012 was Côte d’Ivoire, totaling $130 million.

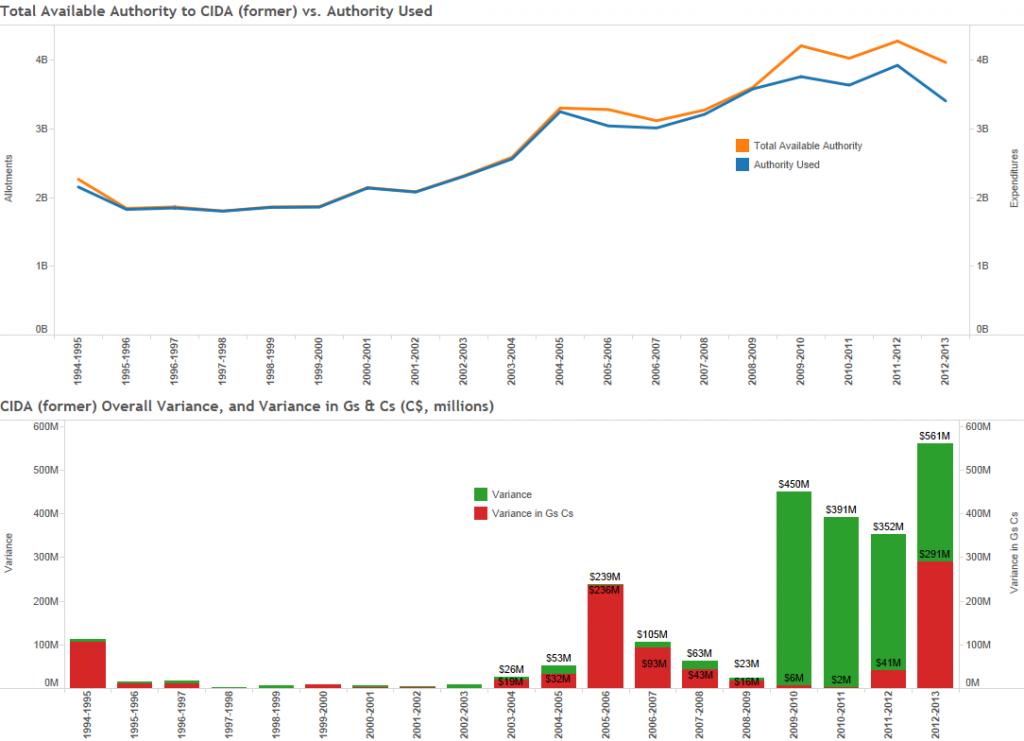

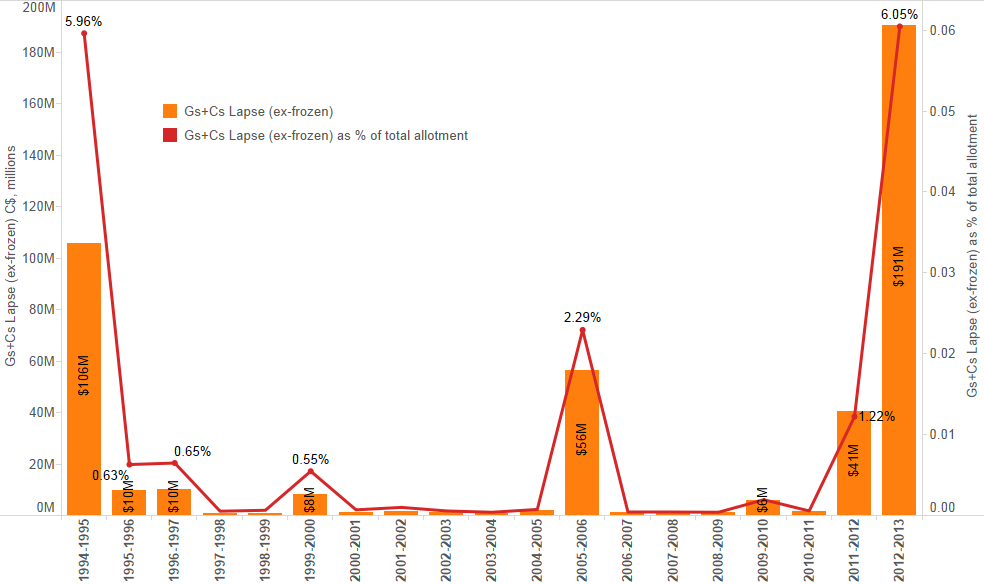

We have seen in previous analyses how budget cuts are affecting aid spending. In forthcoming analyses, we look at the issue of lapses in spending in addition to budget cuts. As figure 3 below shows, recent years indicate a rising trend in development spending lapses (or the gap between authorities made available by parliament and authorities actually used in a given year, in this case by former CIDA, which accounts for the bulk of Canadian development spending). In the most recent year for which data is available, lapses in grants and contributions spending (the main form of development spending) reached a historical high both in volume and percentage terms (see figure 4).

Shifting modes of development financing

The preliminary data also reveals shifts in the modes of development financing within “Official Development Assistance” (ODA, or aid). For instance, much of the increase in bilateral aid is attributable to non-grant aid which includes equity transactions and loans. This type of aid rose 33%, while grant based aid (excluding debt forgiveness) only rose 3.5%. This pattern is also visible in Japan’s large increase, which is driven by increased bilateral lending (which qualifies as ODA).

These trends speak to two broader issues that need further analysis: the appropriate definition of ODA or aid in a context where other forms of development financing are growing rapidly; and the appropriate uses of “DAC-able” aid resources to leverage other forms of financing including private capital, and the resultant balance between loans, grants and other aid modalities.

Figure 1. Where foreign aid rose or fell 2013 vs 2012 (Click to enlarge)

Figure 2. ODA in 2013 vs. 2012 for the largest donors (Click to enlarge)

Figure 3. Trend in CIDA authorities and expenditures (Click to enlarge)

Figure 4. Net variance in grants and contributions expenditure (ex- any frozen amounts) (CAD$) (Click to enlarge)

Recent Comments